How do we tend to land and culture at the same time?

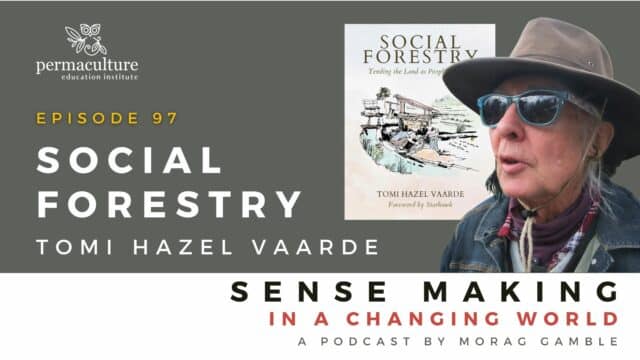

This episode was a conversation of hope for me, exploring the concept and practice social forestry with Tomi Hazel Vaarde – everything from ancient indigenous knowledge to stories of forests. Also Tomi reflects on design – avoiding it being an imposition, but something that emerges from connection with place and community – an incredibly important distinction for a permaculture designer.

Social forestry is the Tomi’s big picture thinking, their frame of reference for engaging in local and bioregional restoration.

“Social forestry is tending the land as people of place. How do we cooperate with each other to do useful things in these places? It’s always site specific, and it’s always culturally specific.”

Tomi Hazel Vaarde is a long-term resident of Southern Oregon and is deeply situated in place and permaculture. He’s a prolific permaculturist – advising farms, stewarding forests and teaching environmental sciences for more than 50 years, even helping Bill Mollison in the first PDC on the West Coast.

Tomi’s latest book (published April 2023) is Social Forestry: Tending the Land as People and Place – an acclaimed guide of practical placemaking advice and ancient lore – a must-have for anyone wanting to have a reciprocating relationship with their communities, themselves, and most importantly their awe-inspiring forests and landscapes.

In this conversation, we also discuss this book and the many projects that have informed its emergence.

Enjoy!

You can listen on your preferred podcast streaming service or on Youtube.

Read the full transcript:

Morag:

Hi everyone, it’s Morag Gamble here from Sense Making in a Changing World and in this episode, I’m joined by Tomi Hazel Vaarde who has recently written a book called ‘Social Forestry: Tending the Land as People of Place’. And so we’re going to dive into a conversation about that. But this is something extraordinary about Hazel, Hazel is a pioneer in the permaculture movement and has been involved in permaculture since I think I was still in high school. So the depth of knowledge and experience that Hazel brings into the story of permaculture and the flavour of permaculture, that is brought through this social forestry approach, is extraordinary. And I’m really excited to have you here on the show today Tomi, thank you for joining me. So I’m calling in from the land of the Gubbi Gubbi people here in Australia. Maybe we could just place ourselves, where are you calling in from? Can you tell us a bit about your place?

Tomi:

This is the Little Applegate Canyon up against a wall of mountains at 7000 feet and it’s Athabaskan Territory. There’s a lot of different tribes that speak with the Athabaskan roots. And these people were called Dakubetede which means ‘people who love the beautiful valley’. And what this valley actually is, is overpriced real estate with very little productivity potential. No water, very little good soil. And it’s a pocket desert on the west side of the Cascade Mountains. So it’s on the Pacific slope, but we get as little as 10 inches a year and as high as 30 inches a year. And it’s been hammered by colonialism. And the Dakubetede were pretty much wiped out and then ran up to a reservation. Slowly things are coming back and we learned how to say the name properly. I have grandchildren who are Athabaskan and I tell them relatives of theirs lived here, which is really a cool thing to be able to do. ‘Hey grandkids!’ They are a Mescalero Apache who are Athabaskins. So in 1830 beaver trappers came through from the Hudson Bay Company, and they took all the beaver – taking out to beaver exposed to the gravels. Thus gold was found. And you know what happens when gold gets found. So it’s been downhill since then. And we’re just beginning to go back uphill again.

But our small farms are failing, utterly failing. From ditches being shut off, and just economics and things. The land here is like, I guess it’s priced for gambling reasons. It’s like crazy! It’s insane how expensive the land is here. It has nothing to do with what the land is itself. So we’re trying to figure out culture in the valley, and luckily, we have built some culture. Just in the last couple of weeks, we’ve had the community theatre skits. Wonderfully put on in something called the Shiny Barn. And so we’ve had a lot of small businesses, some of them are still going. We have a lot of theatre, we have ‘battles of the barn bands’. We have a lot of farm workers, and the marijuana industry just tanked last year. So there’s lots of jokes from mostly from Northern California about, ‘Hey, need any weed? I’ll bring the weed, got weed’ So I mean, it’s just hilarious. Everything. It’s one with one colonial shitstorm after another, it’s just been beaver, gold, timber, grass, land speculation, marijuana, salmon. It’s just a disaster, disaster, disaster, disaster. So what a perfect laboratory to think about social forestry in!

Morag:

Social forestry. Before we talk about what it is and what solution that can bring to this situation that you’re describing, can you take a step back and sort of situate yourself where you first came into contact with permaculture? Because I know from reading your backstory you’ve been involved in wildcrafting and forest care – being out in the forest, being out in nature, connecting people with nature for decades. And then at some point you met permaculture and that became entangled in your life. Can you describe a bit about that part of your journey?

Tomi:

I was drafted to help build and teach the first course on the West Coast, because Bill didn’t know the ecology. I had come out with two degrees from New York State College of Forestry. My Quaker organic farming background, my people have been 400 years in the same villages, which is very rare for blue eyed blondes. So I have this really unique cultural thread that goes right back to the first English colonisation of New England and I can name names. I mean, I’ve had a family story. So when I got to the west coast as a political refugee during Vietnam, medical relief and things like that, I got hired off the street to teach at a junior college in 1971. And of course, without me knowing it, a sign up list was put up and it was titled, Wild Edible Plants and Woods Lore. In other words, it was social forestry in 1971. So by the time we got to 1982, I had already been teaching ecological terminology. And here comes permaculture. And I was like, ‘Ooh, this might be a basket big enough for me to like, find some room to move in. Check this out!’ So I ended up being pretty principal in North America in many ways. I think I am eligible for having written the standard curriculum and I published a pretty famous article on how to certify a permaculture course which I got anarchists from Australia sending me love notes about, that was fun.

So I did a lot of teacher training, I did a lot of that. And slowly, I have left this script. So as far as I’m concerned, permaculture is a tool that we use in social forestry. Social forestry is not a tool of permaculture. Permaculture is like bootcamp, recently arrived pedological and experimental procedures, hopefully, in a wider context than the traditional age of enlightenment science. So yahoo for permaculture! But I have some quibbles at this point. Mostly about the word design. ‘Oh, so you’re a designer? I suppose you want royalties, do you?’ So where’s the social in that? And, yes, it’s an emergency situation. And yes, Uncle Bill kind of drafted us into an army. You know, we got to do this and we got to do it now. And I was like, ‘Okay, sure. Why not?’ Where are we though now? Where has the permaculture movement gotten to? And what it has done positively is a long list. We could go on, we could praise it. I think there’s more permaculture people working in the field than there are from government aid organisations worldwide. They don’t advertise themselves, they don’t wear a permaculture hat. They just had some education and see the world differently. So the part that I really liked, which I was into before, is systems theory. Is looking at things in multiple dimensions, and in complex layered ways. And certainly, that’s what Uncle Bill brought us.

And that was my college education. I got one degree in forestry and the other degree was Systematic Botany. So I studied phylogeny, the evolutionary theory of the plant kingdom. And that taught me systems theory. So that got me kind of set up, along with my village background. Then permaculture arrived so that kept me alive for a while. And now for the last 20 years, I’ve been getting this book out. So I hereby adopt permaculture into social forestry. Welcome to social forestry, permaculture. Where have you been? We’ve been around for 10s of 1000s of years, I would claim millions of years. I could go into that, the anthropology is fascinating. But how do humans work with complexity in useful ways? And that’s the thing that people like to hear from me – guess what, humans can be useful! And the forest misses us. It’s lonely, where’d the humans go? Because we’ve been a presence on this planet for millions of years, in very, very complex ways. And then we kind of went wonky! We went sideways! It’s a problem! And we can go on and on about that. But let’s talk about where we are now and where we can go next.

Morag:

Thank you for sharing that and flipping it and putting that in perspective! I think foregrounding indigenous ways, human ways, long term human ways of being in place, is what I think we all need to be doing right now. In some ways my experience of permaculture is really about trying to reconnect with that somehow, you know, find our ways back into that way of thinking as you were saying. So I think it would be so great if you were able to describe a little bit more about how you see social forestry. If you were to just lay it out on the table for people to be able to say ‘I get what he’s talking about now.’ What is social forestry?

Tomi:

It’s not just tending to land, it’s tending culture. And that’s something we’re not very good at as Europeans. We’ve got this hyper individualism going on. And that has alienated us from nature, which is profoundly a cooperative venture, scientifically, or ecologically. So social forestry is tending the land as people of place. How do we cooperate with each other and with life to do useful things at this moment, in these places? It’s always site specific and it’s always culturally specific. But I think we can boil it down to drainage basins. I gather only Americans call drainage basins watersheds, the rest of the world knows what a watershed is as the ridge line. So we’ll go with drainage basins. If we can reorganise our political thinking on an ecological template, a fractal drainage basin template, and then look at our priorities, we can create a culture – meaning a celebration of place – that inspires us to do the work, and then keeps us grounded through a cultural process, which would be drainage basin councils. Here that would be salmon, beaver, and cultural fire. Those would be the icons, they would be artwork, they would be celebrating, we would understand those are our big three. And we would hold everything in the light of those, for now. While we move into any relationship at all.

So social forestry needs to have that strong ecological basis. I like to say that all cultures and all languages have traditional ecological knowledge built into their language. It’s in their stories, it’s in their fairy tales, it’s in the language, it’s in the silly songs we sang while we were skipping rope. I mean, traditional ecological knowledge is an inheritance of all human cultures. Indigenous ecological knowledge is extremely place based. And social forestry tries to move settlers into people of place, not indigenous – by definition that goes First Nations. But useful habitants doing the work and perhaps coming into relationship through building culture, so that treaties of mutual aid can be established with remnant indigenous peoples. And I’ve managed to do this on a few different continents on the side, much to my benefit. Thank you very much to all the people who have spoken to me. And so I have great hope that we can do this, that we can come into relationship with cultures and with place, and that we need to do both at once.

So how do we build culture? And that turns out to be the number one question that students ask when they come. In fact, it boils down to ‘how do we ever make decisions?’ And so that’s where my hicksite Quaker cultural background becomes handy with committee structures, unanimous consent, speaking to the spirit, and all entities and all peoples. So there’s a spirit aspect, which, if I remember correctly, Uncle Bill said we’re not going to talk about that. But I want to say that all things have spirit, the forest misses us. We can come into relationship with complexity by understanding how much is beyond us and how small we are and how little we know. And then we can do the things that I claim we’re good at and social forestry which is number one, urinate, especially in the right places. Number two, make messes. In anthropology that’s called disturbance regimes. But making messes is a very useful human thing – done right in the right location. And then being absolutely silly – we’re the most ridiculous species on the planet, and oh my gosh, all the other species are highly entertained. We’re so ridiculous. So I mean, clothing, what the hell? And singing and drumming and ‘oh yeah, let’s act silly.’ So those are the big three. I know, there’s a fourth one, but I’ll remember it later. But there are certain things that are essentially human, that are really appreciated by complexity.

And my philosophical statement is: none of our complications are enough to deal with complexity. Complexity is way beyond human understanding or human abilities. We need to take our place. So our prayer, similar to what I just went through in social forestry, is we are idiots! We do not know what we’re doing! Please excuse us, we’re doing the best we can, we accept feedback, gracefully. So before we make our messes, we usually sing that song, to keep us a little sober. And to help us notice. So there’s a great book that came out a few years ago now called ‘Mushroom at the End of the World’, by Professor Xing, UC Santa Cruz. And she points out what noticing is about. And this is in permaculture, this is in that whole observation thing. But in systems theory, you can only deal with complexity by noticing emergent properties of complexity. You’re reading the edges of things. You just notice a bird move or you notice something just happened. And if you have a story in a song about that, you might notice what that special notice is about, you might go, ‘oh, oh, hey, we should talk.’ So this is delicate. It has to do with helping each other stay centred. Keeping our focus on a larger world, not just the human world and especially not the individual. Very challenging. So okay, I went on for a while.

Morag:

Thank you for describing that! And as you were speaking, my mind was imagining how you might begin to cultivate that kind of cultural insight. How do you invite people to come and play with you in that space? So say, for example, where you are now and you’ve described the destruction that’s happened. What’s your invitation to people in that area to come and participate in this?

Tomi:

I help people discover who they are in relationship to nature and to other people. And of course, now a big thing is pronouns. So, my pronouns professionally are them/they, but number one, the Quaker pronoun, which is Friend. ‘Friend speaks my mind’ is a famous Quaker phrase, very inclusive. So there’s a pronoun so first of all, what gender do you think you are? Second, what are your passions? Third, what are your propensities? So you can kind of map humans as soon as their personal experience, personal as it is, in relationship to other people. And then I encourage them to be part of guilds. So guilds sort of like mediaeval craft guilds. Guilds in social forestry are rangers, mothers who are herbalists, bodgers make things. Charcoal liaise are charcoal people. There’s a few more. Hunters. The rangers are big because that shows up in a lot of science fiction. The Ranger idea has been around and ‘I went to Ranger School, I drive a Ford Ranger, and I drink voodoo Ranger beer.’ So anyways, you might think I’m a ranger. A ranger, for instance, is an in between, I have a intersexual body type and I have a certain personality and that’s why I ended up in ranger school. I can help other people understand, ‘oh, you have these passions, you have these propensities, you have these skills, you have this cultural background. Might you be interested in…?’ And then I get people to talk to each other in these guilds. The guilds send delegates to the drainage basin councils and then managed to make decisions, because we have feedback from a whole bunch of different angles that different human types have put together. A lot of this I got from teaching at Dihu University a multi-tribal college in Davis, California in the 80s. Because we were dealing with people off the reservations and they were completely confused how they were going to fit into modern times. Luckily, we had Mohawk educators from New York and others. So this is the Iroquois nations who came to us and taught us. First thing you want to do is find out what a person’s passion is. Forget all these academic testing things. You want to know, what do you love? And then you want to feed it. ‘Oh, okay. leatherwork.’ Alright, here’s all these tools, here’s all these materials, go for it. And if you do that, they come, people come forward, they feel seen, they feel loved, they feel taken care of, and they start to participate. Because now they have honour, they have creativity, they’re being brought into the circle. And they’re being told, ‘You’re cool. And we want to work with you.’

Morag:

I just want to jump in there. Because where do you differentiate? Culturally, we talked about before, as the individualistic culture, that is a big part of the problem. And how you’re describing is now it’s like focusing on nurturing this individual. How do you find a way to bring that individual back into that wholeness, like you’ve just brought them up? So how does the individual not become the kind of the independent or separate person when they’re fed like that? How do you, through social forestry, weave them into the story as opposed to just creating a whole lot of individuals who are following their passions and not connected?

Tomi:

Well, I think we do it through place. This is where place comes in. So if you commit to place you become a people. And if you can bring together the cultural aspects that we all have, even though we’ve been traumatised and colonised and commercialised, commodified. If we can bring together the threads of narratives in place, and dedicate ourselves to the work in a place, the place will teach us. And this is what indigenous knowledge repeats over and over again, just look at the shape of the land. Check out where we are, this is this place. And this is how we are as a people in this place. Now, when you’re dealing with indigenous people, you can help them reconnect with their tribal backgrounds, and you can do adoption. So that’s something we don’t know much about – cultural adoption, not family adoption. So that’s tricky, but it’s something that can be done. And so, if we can understand that place is adopting us. It wants us. It wants to talk and dance with us and sing with us. Then we can start to feel like a people and we can start to be a people and we’re having that in the Little Applegate. This is what I was talking about earlier. We have certain cultural things going on that are building this sense of ourselves. And I have a folk song I sing about Bunkum, a mining town, a ghost town. So that’s part of it. Okay. But you’re asking a very important question that’s complex, like how do we become people of place? Well, ‘there’s a page in the book of the 10 steps to’ and the first thing is take a permaculture course in your place. Get oriented! You need to know so much! All the plants, all the animals, the water, the soils, the geology, the weather. So how do you do that? That’s why this book is chock full of posters, teaching posters that were made for permaculture courses.

Now as I said before, trying not to emphasise permaculture, but social forestry. And understand that permaculture is a tool in a greater work. And how we get there, it’s going to be through relocalisation, decentralisation, and oh my gosh, I believe we’re in it right now. You heard about the banks collapsing in America? Have you been paying attention to the news? I’ve been through this a few times in my life. I think I’m noticing something. And I want to tell people good news, that we should not be freaking out. But we should understand what the long range priorities are. For survival, and not just human survival, but complex biodiversity. How do we do that? Well, I use systems theory a lot. So that’s the book ‘At Home in the Universe’ by Kauffman. And it’s the book ‘Chaos’ by James Gleick. I have a lot of mathematical scientific background. So I have a little bit too much fun with this. But we are at a phase change. We can’t see what’s on the other side. But we’re doing some of the things that will build the new organisational structures, we just don’t know precisely what they are. And we don’t know where to put our energy. I say go with the rhythm, the tune and the dance and the heart. And that’s the best we can do. And do it in place! Because that’s the only thing – place-based attention to ecosystem functions. I’m actually hoping through a series of transitional cultural artefacts like stewardship contracts that we can get subsidy in first phase of social forestry, because there’s some serious ecological repair that needs to be done. Roads to bed, forest to stabilise, reintroduction of fire, helping the salmon come back because of nutrient cycles. So I just threw a whole bunch out. Okay, but kind of just to give you a taste of what we can do now, where we are. And I usually say start with the children’s watershed pilgrimages. Let’s walk the watershed.

Morag:

Yeah. So that connecting to place. I mean, there’s lots of different questions that were arising in me as you were speaking and one is about ways of connecting urban communities that don’t have that. When you look out your window you can’t see the landscape. I mean, where I am here, I can look out here and I see the clouds pop off the top of the mountains and float off and I have that perspective from being out here in the countryside. But if you’re in an urban environment, and I grew up in a city, there is far less of that. Bigger picture, your ability to see the watershed, you see your street or the next house over. And so what you’re saying about actually going on a pilgrimage, I think that is a beautiful place to begin whichever part of the world you are dwelling in. I was really interested to hear you talk about beginning with joining the dance, because often when a community will come together, they’ll go out and they’ll start to plant trees. So where is the place to begin? And I guess there’s no one answer to that either. But what are some of the places to begin that you’ve noticed? You’ve mentioned the pilgrimage with the children up into the watershed. What other things have you noticed that have really been a way to connect people with place?

Tomi:

Luckily, in Oregon in the 80s, Governor Kitzhaber subsidised watershed councils, this the Americans. And those watershed councils did a tremendous amount of information collecting, like any good designer might do. And I’m afraid all those rolls of maps are sitting in closets at this point because the subsidy was removed. So the continuity during transition, of having statewide, province wide watershed awareness, requires some help. I’ve actually spoken to provosts at universities and stuff, who of course always want to know if I can get a big grant for them as soon as possible. But I’m like, ‘No, we have what we need.’ The information has been gathered by some government entity or some academic entity. Our neighbourhood needs to put that closet of maps together, so that we do understand where the watershed was, even if that even if that ridge line got paved, or McMansioned, and as we say. And then do the walk on the watershed as close as possible. And just by doing that, we see it, we feel it. I’m talking about very small watersheds, you know, let’s do a couple of 100 acres, you know, 100 hectares or something. Let’s look at a small watersheds. And let’s try to understand it as an entity. Eventually, I think we need shadow governments that are watershed based, that are drainage basin based. And those shadow governments are going to suggest to the idiot political situation that it’s do or die, folks. And here’s where we are, let’s get properly organised on a watershed basin basis, and reconfigure our actual representative governments so that we are on the ground that way.

That’s a lot of time for people right now. And the big part of the urban question is ‘who has the time?’ Well, okay, I’ll get one of my reputations of being a bad auntie and saying the inconvenient things, I would say we’ve been in a phase of surf and dodge. This is what we’ve been up against. And just to stay alive, I also call it triage. But we’re about to enter and we are already in I think, a phase of salvage and squat. In America, there’s huge amounts of empty commercial property adjacent to degraded forests and riparian areas in urban jungles. And these areas are eligible for social forestry work. We can do brownfield mushroom remediation, we can do tending, we can do charcoal making, we can do species surveys. We can designate remnant ecological places like cemeteries or temple grounds, land too steep to build on. So both Portland and Seattle in the Pacific Northwest have lots of forests. They’re just on super steep ground. Portland has a trail system that has an urban pilgrimage that you can walk, I think it’s 50 miles in a circle connecting parks together. So that’s progressive. But I’m more radical than that. I want to get granular down to actual water, actual drainage basins, actual boundaries, and start doing what we can where we can. And indeed, the City of Portland, has subsidised the recovery of a large warehouse in a brownfield area in Northeast Portland. And all of this is happening because the last podcast I did was with Peter Bower with rewilding and I asked him that question. He was on it. Oh, yeah, we got it. We’re doing it. Boom, here, there. I was like, Oh, good. Like to hear that. I’m not dead yet. Stuffs happening. Cool.

Morag:

I think the idea of having these watershed councils with shadow governments is a really key part. Because what I see around is that there are people in our watersheds who are doing amazing work, but they’re not necessarily all talking to one another. If there was a possibility of having that work cross fertilising, supporting, singing up what’s actually going on, and not maybe even competing against the limited funding, some way that would be transformative. I think, in the moment and, and give us some somewhat of a quantum leap in, in where we’re going with this accent, it feels really potent to me.

Tomi:

So I’ve tried this in Ashland in the 90s, I had meetings with multiple nonprofits present. And we’d go through the meeting and I would explain what the potential is and what we might be able to do. And everybody says, great! Time for dinner. So I’ve come to the conclusion that we need to do set and setting. That this needs to be done really well. And I’m going to go back to the Pantheon in Greece, I’m going to go to Ivan Illich ABC, I’m going to talk about cathedrals in Europe. These are called minomic architectures. So a proper Watershed Council is going to meet in a sacred space, the druids and their tree alphabet. And they’re going to be surrounded by icons. And these icons are going to keep people oriented. Because if you can point it to one icon and show its relationship to another one, brains rewire. So this is why my book has 30 posters in it. I imagine that if we have these systems posters up on the wall, surrounding us, while we’re sitting in counsel with each other, we’re going to stay better oriented. If we’re helter skelter, and we can’t quite figure out an agenda and we’re competing. I’ve been there, I’ve seen where it goes. We need to come together in a whole different way. And that way includes indigenous peoples starting the meeting, making a gratitude. Let’s spend some time on the gratitude. Let’s get oriented and let’s understand who we are, where we are. Then let’s try to be – this is a Greek word I believe – sophisticated! Oh, okay.

But anyway, systems thinkers. Let’s look at this. It’s been a major tool in my permaculture course teaching, is to have these multiple posters up and a laser pointer or a long willow stick and be able to say, “See, look how this is connected to this and check this out over there.” I’ve seen people have steam coming up their ears, because their brain just went into high gear. We think in symbols, and this is nature and madness. Paul Shepherd says nature and madness. For children to be let out in nature’s stings, scratches and falling out of trees and all – slime, goo, bites, the works – a human child develops a symbolic deck of cards in their mind. Some people who haven’t spent enough time in nature are missing some cards, therefore they can’t do holistic thinking. If we can’t sink as full humans embedded in nature, we’re not going to get very far. And that’s part of the children’s pilgrimage. But it’s also that we can fill in some of our missing cards, by taking a good permaculture course, or by having these icons up or by meeting in an artistic holistic place.

And I will give a little mention of Allan Savory here and holistic management. He has the elderly gentleman angst at the moment because no one’s listening to him. So he kind of spouts a bit these days, the last interview I saw. But he makes a very good point, which is, cultures have learned to think holistically but not manage holistically. It’s another jump. It’s another paradigm to go beyond that. Good that we’re getting our holistic thinking together. But we now need to make some decisions. And that’s a matter of management. I’m suggesting that social forestry is a way we can start to do this, because we’re dealing with hammered lands and downtown. And we can make some progress and in the process, develop culture, do culture tending, learn how to work together, learn how to meet, surrounded by our icons, and do symbolic thinking. Because words are the last thing to come out of our mind. All of our dreaming, all of our planning, all of our trying to solve unsolvable problems is done in a completely magical, symbolic way. And back to your liking the idea we have to dance into this thing. So there you go, a few more little clues about we need some elders, I don’t have a lot of cohorts. They are still doing pretty well.

Morag:

I wonder too, I don’t know, it’s not a reluctance to join, but an inability to join is coming from the deep level of anxiety that people feel around what’s happening. Just like frozen in the lights of what we see going on. And I know that you do work with Starhawk. And I wonder whether you could talk a little bit about that eco anxiety and your response to it or your collaborating with Starhawk.

Tomi:

I think we all have ancestors who were forcibly removed from social forestry. And the trauma that we all carry as settlers, has deracinated people, is deep. It’s in our art, it’s in our language. For instance, English itself has been degraded. The English language is not a great language for us to be talking about what I’d like us to be doing. It’s lost a lot of complexity. It’s lost a lot of art, a lot of dance, and my hicksite Quakers spoke Quaker plain speech and that’s older English with the ‘the’ in the ‘thou’ in the phrase-ologies and so, so there’s a whole language thing now, what was your question again?

Morag:

So it was really around how do we get past? How do we support people to get past this feeling stuck or hopeless to be able to actually engage in this work?

Tomi:

Well, first I want to, I want to just give everyone some love because we’re traumatised people. And we come from traumatised cultures. And I want to suggest but that’s not all bad. Because there’s some threads in that trauma that are beautiful, and let’s weave them, let’s weave them into a new tapestry, a multicultural tapestry that’s focused on place. Bring all these different threads together for healing, and work on the trauma and actually acknowledge it. And I mean, again, this goes back to discussions of freedom and The Mushroom at the End of the World. The modern American concept of freedom is completely misplaced, quite different from the concept of liberty. Liberty is the ability of cultures to make their own decisions, sovereignty. Freedom has been co-opted by Freud and others for purposes of commercialization and advertising. So freedom now is ‘rip off everything you can grab. It’s your right, it’s your freedom to steal as much as you can steal. It’s how the world works! Didn’t you know?’ Very bad science, excellent propaganda, and really good for imperialism. And for justification. Bad, bad, bad. So we need to have that conversation, we need to point out where we’re a little misdirected. But actually, there’s a good part of this story. So let’s go there and let’s start using these ideas and start to understand what the difference between liberty and freedom is. And then let’s start to talk.

So I had a permit system for roadside gathering with the Forest Service with the federal Forest Service. And it turned out that we couldn’t close any gates because of commerce laws. And so all the improvements we made on the roadsides – basketry materials, compost piles – anyone could drive up there with a pickup truck and just take it away. Because it’s theirs. Well, guess why that sense of freedom came up? Because the king took the villages away. So we’re only stealing from the King, who stole our culture – that’s trauma. Let’s look at those fairy tales. Let’s look at those operas. Check it out, those are attempts at healing, that’s a dance that we can benefit from, if we can do it culturally.

Morag:

It’s a really interesting part of this exploration that it’s not saying all of that story is bad, we have to replace it with something else. It’s how do you re-weave different threads into that and allow other threads to dissipate that are no longer serving our purpose. I think that feels like something that we can grasp hold of. It really is about finding the parts of our story that we need to carry on and parts that we need to retell. And also I want to come back to that language piece that you mentioned. English language seems to have lost a lot of the nuances of place in terms of the 100 different words of a forest or the smell of the soil whereas I think that is a huge part of the healing and of moving forward is enriching our language with that with the nuance of place. I wonder if you’ve done anything in that kind of realm and have any clues of how we begin to do that more.

Tomi:

There’s a big movement on the West Coast of changing place names. Because a lot of the place names are evil. And that has been quite a healing conversation to start to rename things and re-understand things. But I’m trying to remember the author was it Langlands who wrote that book about all the different names for a creek this big or rivulet, all the Scots terms. You know, all the Irish terms, all place based. Well, I think we can start building those things. People want to know what ‘gulch’ is. Right. That’s a desert term. It’s a forested desert term. Well, it could get pretty local if we start to talk about different types of cultures and gave them different names. So the children would learn these things. Again, this takes time.

Morag:

New stories, new songs.

Tomi:

Yeah, bring that stuff back or find it new. So here we have indigenous languages still intact. And that has helped a lot. And so the name of bear, or the name for dragonfly. So the river here that runs through Southern Oregon, is called the Rogue River, which is basically calling it a Thieves River, the rogue. And it had to do with what the indigenous people were called rogues. But the people are Dialagamun (?) which means people that have dragonflies river. So, when the publisher wanted a map in the book, I had to work with the cartographer. We need to change this and we need to change this, and I barely was able to get going. I mean, I got some of them. No, luckily, some things are being changed on their own. But this is an ongoing thing that lots of people are working on with input from indigenous tribes in Oregon. And we’re slowly changing a lot of place names, big help, and we’re starting to teach indigenous languages to all to children, what the name for bear is, etc. You know, like know why this place is called that. Why are they called that? What happened there? There’s a lot of history that’s missing. And, again, all praise to my family, especially my mother for telling me the stories. And for always going for picnics in cemeteries. A lot of wildlife in cemeteries, butterflies, you know, I didn’t know what she was up to but I think I got it now. She should go for picnics in cemeteries, for sure. Where the hell are we? What happened here?

Morag:

I think it’s a curious mind, isn’t it. to have the noticing mind, like you were talking about before. To be able to enter into that space? To be in conversation? And to be in noticing? And to and to find a way? Yeah, I think maybe we could just sort of come back to that question you had around design. So you have a new understanding, you’re noticing. So where do you find the rub with the concept of design, if it’s coming from that place? And you’re really thinking about ‘I understand this place and now I’m going to think about how to maybe regenerate this place’? Isn’t that the design process?

Tomi:

I see it more as a process of discovery than a process of design. I think design is just loaded. It’s not that bad. But I’m trying to do some nuance here, right through my elder status as an aged permie. If you think you can put a system together that’s going to work, I would call that ‘quick fix.’ So I’ve now changed how I used to talk about design, I’ve changed it into a three phase process, which all happens simultaneously. And that’s quick fix triage. Retrofit – which is what we think of as traditional permaculture design, and ultimate – which is visionary. So I think we really need to get to the visionary stuff first. And that it’s very difficult because it’s not in our language abilities. So I like to go to the land that teaches us the vision. The vision is in the shape of the land, in the shape of the drainage basin. That is the vision. What does it look like? Is it a heroic landscape? Is it a diffuse landscape? So it has qualities, it has personality, it has lines and shapes, and that’s place. And so if we can come into relationship with ultimate visionary thinking, then our retrofit work, and especially our triage work, is going to be constrained because you don’t want to do anything. That’s going to compromise ultimate. If you compromise ultimate, bad idea, look what has happened. Not good. So we need the ultimate, which I’m calling beaver, salmon and fire. And then we do the retrofit, which I claim is squat and salvage. Not exactly a design process. It’s kind of helter skelter. I call it the ‘aggravation during the phase shift.’ How do you surf and dodge? That’s not design, that’s surfing and dodging. And oh my gosh, we need to know and we need to notice. We need to be really supple and agile. Talking and not hung up in ego and not hung up in too much of a linear process. If you go back to Heidegger and those German philosophers, they were big on doing things on purpose with intelligence and intention, and thus we are enlightened and we are knowledgeable. This is the Age of Enlightenment, and we have data and science, and therefore we are designers and we can fix it. And I’m like, ‘No, you can’t fix it. You’re just part of a process.’ We all really ought to understand where we are in that process. So that’s why I flipped this and put vision right at the top.

Morag:

Thank you for clarifying that, that makes so much sense and really does bring the imperative of people who are in the permaculture process to really open up from looking at what’s going on in their backyard, or in that plot that they’re looking at. Which I hope that any good permaculture teacher begins there, in place, and then gradually brings it down into the nuances of what you can do in the piece that you’re in – but with that bigger picture. That’s what I hope good permaculture courses are, in my view, trying to help people to connect with. I really liked the way that you’ve described that, it makes it very clear, thank you so much. I realised that we’ve been talking for quite some time now. And I wanted to respect your time and I think we just talked for an hour. So where can people find your book and what would be a call to action that you would like to share out to for people to ponder on or get involved in?

Tomi:

Juggle grandchildren! So the book is going to be available from so many different sources. If you’re in North America, you can do it through our fundraising campaign, because that helps us to pay for the artwork. But that’ll be over, you know, in May or the middle of May. And after that, probably best to buy directly from the publisher, because that helps all of us, rather than Amazon. But that’s where you get to book. It’s an actual publication that’s in the publishing industry. I’m kind of in shock, to tell you the truth, because I self published a book 30 years ago and I hardly sold maybe 2000 copies in 30 years. I think I’ve already sold 2000 copies of this book or someone has sold it. So it’s available very easily. It’s a reasonable price, I’m so happy about that. And what can people do? Figure out where you are. And this is kind of hard, right? Because with rents and with jobs and with everything turning over, people are being turned into capital – mobile capital, instead of actual humans of place. So making an intention of placeness is very radical. And I would say I have a few different places. There’s a place I live here where I’ve been for 50 years, the Sicsous (?) mountains. But then there’s the cities that I have roots in that I have cultural ties with and those are my places too. So I think we all have multiple places.

Morag:

I think some people get hung up on the fact that ‘I’m a bit mobile and I can’t land anywhere.’ We could land in multiple places. I think that is a gem of a gift. Thank you!

Tomi:

Yeah, totally. Absolutely. And we’ll know so much more. I’m again, I don’t know how I did it but I got to a few different continents, and oh, boy, that really helped me a lot. I got some perspective. And North America is a big place and I’ve gotten around. But then at home on the ground, I have walked 1000s of miles. I know this place. I love this place. And the Sicous (?) are a world class biodiversity hotspot that has made it through major climate changes in the past. So I’m counting on that. It’s kind of a hard scrabble place that survives. And it has to do with how broken up it is.

Morag:

Well, thank you so much for joining me here today. The links that you’ve spoken about I’ll pop down in the show notes. So for anyone listening, go and have a look down there, you’ll be able to find out how to connect with the crowdfunder if you’re listening to this in the next few moments. If you would like to get the book, I’ll put the links to that. Any of the work that Hazel’s got, I’ll make sure the links are there. And also some of the references that you talked about, as we were going through the conversation, I’ll find those and drop them in there, too. So thank you so much. And I really wish you all the best with this book, and I’m going to be putting my order in to get a copy as soon as it’s released. I really look forward to that. Thank you so much for bringing that out to the world. I heard you say it’s been a couple of decades in the making.

So just as one final little question, I’m trying to wrap up. But what is your writing process? Can I just ask you that? Like, I’ve been talking to lots of authors lately and really curious about how you step into that space around you? Do you sit down all at one go? Or it’s just like a gradual infusement? Or how do you get to that point of distilling this into something that you can go ‘right, I’m ready to hand that out into the world’?

Tomi:

Well, at my age, you better damn well have a notebook next to your bed at 3am. Old people do, they wake up at 3am and they have ideas and they jot down notes. But I’ve had a lot of experience with curriculum and academic writing. So I do kind of organise things. But this book went through four very different manuscripts and a dozen editors. So there’s quite a process. But the biggest thing for me, I want to thank my ancestors, is learning how to clear and allow things to flow through to really believe in writing things down, and then editing and editing and having it checked. I mean back to things we said before, I don’t believe any of us on our own hold truth. Truth is only held in culture and in place. It’s not held by individuals. If individuals get all hot headed, because they think they’ve discovered something, the Quaker elders would always say, ‘Oh, you have a leading ticket to clearness committee, we’ll check it out.’ So it’s a community effort.

But I myself, in the middle of it, am an administrator. Not a designer. I’m an administrator. And I’m letting things flow through and I’m gathering resources and then I rearrange it, rearrange it, rearrange it. So it takes a while. And it helped that we used a lot of this material in teaching, and got that feedback, not just editors, but taking it out into the world, seeing what you get, bringing it back, figuring out what to write.

And how did I know when it was done? I just said, I’ve had enough. I’m declaring it done. And then everybody stepped up. It was kind of amazing, really! I mean, I didn’t look for a publisher, they called me! This has been my life, I keep getting drafted. Uncle Bill drafted me. I mean, whatever. I’m just following orders. I’m not following orders, being inspired and yeah it’s great.

Morag:

Oh, thank you for sharing that. I really appreciate you unpacking that a bit for us because everyone does it differently. And I know that there’s a lot of stories that need to be shared and finding how people are finding their way into doing that really does help to bring it into the light. Thank you so much.

Tomi:

Lovely conversation.